Blog

What is Earth Day?

Read moreKasungu community helps build a fence for their future—and elephants’

by Charles Mpaka

For almost five years, men and women living close to the border of Malawi’s Kasungu National Park have demonstrated community engagement’s power in conservation.

In total, 543 people have found employment helping to build a fence—a project that aims to reduce human-wildlife conflict. These individuals are earning an income and learning valuable technical skills, all while playing a vital role in protecting their families, their livelihoods, and wildlife.

When completed, the 130-kilometre solar-powered electric fence, stretching from the park’s southern section to the north on the border with Zambia, will enhance the park’s security and prevent wildlife’s destruction of crops and village infrastructure.

IFAW and the Departments of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) of both Malawi and Zambia initiated a project combatting wildlife crime in the Malawi–Zambia landscape in 2017, and community involvement has been at the heart of our activities ever since.

‘No wildlife conservation work can be successful if people in villages bordering the national park do not have a part in decision-making regarding the park’s management and the conservation activities,’ says Phillip Namagonya, Community Engagement Officer for IFAW in Malawi.

Anthony Chatama, Vice Chairperson of Kasungu Wildlife Conservation for Community Development Association (KAWICCODA), a government-registered cooperative of members from all the villages bordering the wildlife reserve, says since communities had a hand in the degradation of the park, they also are better positioned to contribute solutions for its restoration.

‘One of the things the IFAW project has done is to listen to us and understand why people have been invading the park,’ Chatama says. ‘I think consultation has enabled the authorities to understand our challenges and guided them on interventions so that people no longer turn to illegal access of resources in the park for survival.’

The 2,100-square kilometre Kasungu National Park, Malawi’s second largest, was a thriving wildlife reserve from 1970 when it was established, having boasted over 1,200 elephants and thousands of other animals at its peak. However, years of rampant poaching in the transboundary conservation area from the mid-1990s resulted in a drastic decline in the elephant population, and human encroachment degraded the park’s habitats.

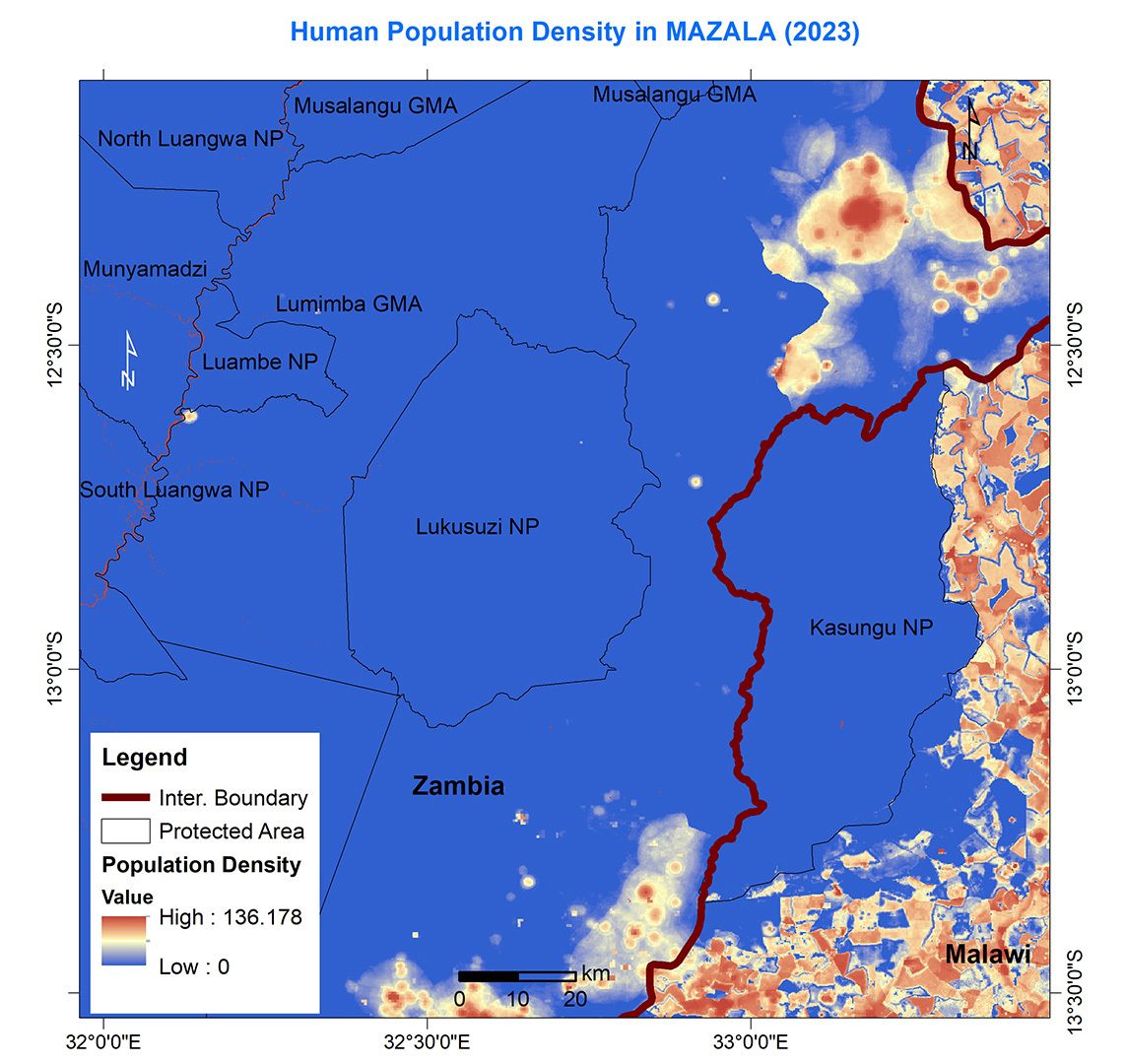

The human population has been rising rapidly beyond the park’s borders, resulting in an increasing demand for farmland to support livelihoods. In 1998, Kasungu District had a population of just over 480,000 people. By 2018, the population had almost doubled, reaching 842,000, according to the 2018 National Population and Housing Census figures.

With sections of the national park remaining unfenced for decades, communities opened farm fields in the ‘buffer’ zones—in some cases, cultivated land begins just metres beyond the park boundary. People and elephants live closer together than they ever have, inciting human-wildlife conflict.

When finished, this project will benefit the people in the areas experiencing human-wildlife conflict by protecting them from the animals that stray out of the park. This became clear during a short interruption that stalled construction. Villages experienced frequent elephant raids on their crop fields and homes, which caused injuries and damaged houses. First and foremost, the fence will keep out the elephants, as it has done in the other villages where the work was completed.

As an additional benefit, the project provides temporary employment opportunities. Its implementation policy hires people from the villages through which the fencing work passes. This gives community members a new source of income, enabling them to invest in boosting their livestock and crop farming and strengthening the community’s sense of park ownership.

IFAW and KAWICCODA are implementing climate-smart agriculture and beekeeping projects to enable more sustainable livelihoods. These provide an alternative source of income and reduce the community’s reliance on extracting the park’s natural resources like grass and wood.

For Skwiza Mwale of the Kaphaizi area, the fence has brought peace to her community. One night in August 2022, elephants invaded her community, destroying a storeroom and eating the maize it contained. IFAW hired Skwiza to work on the fence, helping her raise the income needed to replenish her maize stocks.

Since the completion of the fence in this area, there have been no elephant raids in her village.

‘Trying to keep elephants off when they are in the area is a scary job,’ she says. ‘We hope the fence will keep them away for good.’

Building the fence doesn’t just protect communities; it benefits Kasungu’s elephant population, too. Incidents of human-wildlife conflict can be deadly for both parties involved. At IFAW, we work to protect these critical ecosystem engineers, as healthy elephant populations support biodiversity and the continued presence of natural resources.

IFAW and DNPW Malawi expect to complete the remaining 42.5 kilometres of the 130-kilometre elephant-proof fence by June 2025.

Charles Mpaka is an environmental journalist in Malawi.

Every problem has a solution, every solution needs support.

The problems we face are urgent, complicated, and resistant to change. Real solutions demand creativity, hard work and involvement from people like you.

Unfortunately, the browser you use is outdated and does not allow you to display the site correctly. Please install any of the modern browsers, for example:

Google Chrome Firefox Safari