Blog

Kenya’s Lamu Port can balance economic development and environmental protection

Read moreWhy removing artificial water sources benefits elephants and their habitats

Written by Peter Borchert, writer and conservationist

Elephants need water—lots of it. Depending on their size, they must drink 100 to 200 litres at least every two to three days to avoid potentially severe dehydration. In hot weather, an elephant can lose as much as 7.5% of its body mass daily due to dehydration. So, water availability, particularly in dry seasons and drought, is critical to elephant survival.

Water dictates where elephants roam, limiting their foraging range to areas close to rivers, lakes, pans, and other wetlands. For example, elephant herds with calves stray no further than 10 kilometres from water.

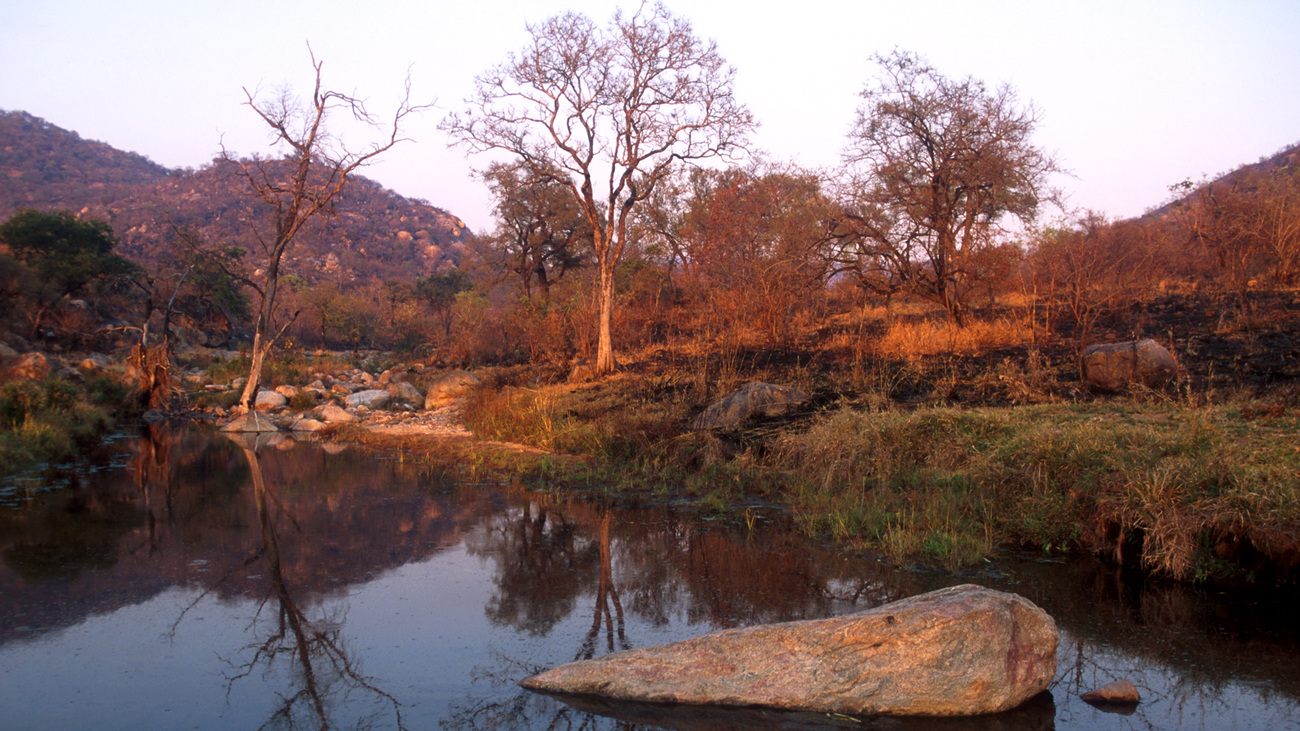

If left to their own devices and given enough space, elephants migrate in response to rainfall variability, prompting predictable seasonal land-use patterns. For instance, in dry times, elephants will gather around perennial rivers and other permanent water sources. At the same time, in the wetter months, herds will disperse widely to take advantage of seasonal streams and ephemeral pans. Such natural ebbs and flows allow riparian vegetation to recover from the intense feeding pressure of elephants and other browsers.

However, human-created watering points disrupted this cycle in one of Africa's foremost conservation areas, Kruger National Park. This practice of providing access to permanent artificial water sources began in the 1930s and accelerated dramatically in the 1960s and 70s. Over this time, more than 300 boreholes were drilled, and 50 dams were constructed in Kruger.

The motivation was to improve wildlife numbers, and initially, it was successful. But there were unintended consequences—the constant availability of water interfered with the natural movement patterns of elephants, resulting in unsustainable damage to vegetation, which eventually led to the culling of elephant populations—which continued until the ideas behind IFAW’s Room to Roam initiative began to take hold. Conservationists now think of elephant conservation in a new way.

We need to go back in time to understand why this was done. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, elephants and other wildlife were severely depleted across southern Africa and, in some cases, driven to extinction by excessive hunting. The rinderpest epidemic in the 1890s also devastated hooved animals. Therefore, wildlife densities were low in much of the land that came to be set aside for conservation. For example, some experts believed that in the early 1900s, there could have been as few as 6,000 elephants across the region.

Wildlife managers at the time saw two opportunities to rectify the situation: to install fences to confine and protect the animals already there and provide them with year-round water, increasing their chances of survival and growing their populations. Also, the animals would be concentrated in areas where tourists could easily view them.

The thinking made sense, and the water began flowing to a rapidly growing network of reservoirs. Elephants and many other species were drawn in numbers to the water, and their numbers grew with plenty to eat and drink.

However, the benefit to the animals and the game-viewing public came at a cost. Elephants and other animals now had little reason to disperse. Very quickly, the increased wildlife density, plus the constant activity and feeding pressure around these artificial waterholes, led to the depletion of the surrounding vegetation, exacerbating food scarcity, especially during droughts.

By then, any options the elephants might have had to explore food resources further afield had been removed due to fences and human settlement. With elephants never having to travel more than five kilometres for water, bare land around waterholes became the norm. Trees disappeared from the horizons they had once dominated.

Agricultural logic—keeping animal populations below the limits dictated by the land—dominated wildlife management thinking of the time. So, whatever threatened to throw off the ‘Nature of Balance’ had to be controlled. For some three decades, this dogma of controlling numbers to keep them below the land’s ‘carrying capacity’ ruled. This was calculated at ‘about one elephant per square mile’ for elephants, not based on science but merely on opinion.

So, culling was deemed the solution. From the 1960s to the 1990s, wildlife managers believed that reducing elephant numbers would restore ecological balance. However, it failed to address the real issue—human interference with natural movement patterns. And so, despite the killing of tens of thousands of elephants in Kruger and elsewhere across southern Africa, tree loss and land degradation continued.

Furthermore, after culling operations, the elephant population soon recovered, rapidly expanding once more because of the continued availability of water and the presence of fencing, which eliminated the natural role of droughts and migration in controlling their numbers. Water provisioning also increased antelope populations, leading to overgrazing and altered ecological dynamics. Scientists began to realise that culling was not a viable solution.

Elephant birth and death rates fluctuate naturally because of variations in food and water availability. These resources also impact the seasonal migrations of herds. The assumption that elephant numbers caused habitat destruction was flawed and lacked proper scientific backing. Over time, a better scientific understanding evolved regarding the ecological processes at stake, and the impact of elephants on vegetation was found to be more closely linked to human interventions, such as artificial water sources and fencing, as they disrupt natural population control mechanisms.

This new thinking began to prevail despite strong opposition from some quarters. The late Professor Rudi van Aarde, head of the Conservation Ecology Research Unit at the University of Pretoria, led the way as he and his colleagues conducted in-depth studies of elephant dynamics in response to water provisioning, the presence of fences, and the practice of culling.

Today, elephant numbers in southern Africa’s protected areas remain relatively high—but interventions are needed to counter potential habitat degradation for the species across the continent. The key is that these interventions should address not the symptoms (elephant numbers) but the root cause of habitat degradation—water provisioning and fencing.

Without interventions to protect the landscapes, elephants will continue to be confined to restricted areas, leading to long-term ecological damage, which, if unchecked, may negatively impact biodiversity.

So, rather than controlling elephant numbers through culling, Rudi and his team argued, with science-backed justification, for a focus on restoring natural limiting factors. Artificial waterholes and fences must be reduced to allow seasonal migrations that regulate populations and their ecological impact.

Management efforts in Kruger now support this approach. In 1994, 12 boreholes were closed, and one earth dam was drained. Culling ceased in 1995. Today, more than half of the artificial water points have been closed.

Also, some fences have been removed under transboundary conservation agreements. Consequently, the modelled population growth has slowed to an estimated third of its previous rate.

Longer-term conservation strategies for Kruger and other key landscapes must continue prioritising the restoration of space rather than population control. By expanding protected areas through transboundary conservation projects, connecting them via corridors and buffer zones embracing adjacent communities and their land, we can create ‘megaparks’ to accommodate elephant ‘metapopulations’.

These vast, interconnected conservation areas will allow elephant numbers to naturally ebb and flow in response to seasons and more extreme events such as drought and floods. Several initiatives in southern and East Africa already link reserves across borders, fostering natural population dynamics. The Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park (GLTP) was one of southern Africa’s first formally established ‘peace parks’.

The IUCN developed the peace park concept in the 1980s to embrace transboundary conservation areas dedicated to promoting and commemorating peace and cross-border cooperation. The 13.5 million-square-mile Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area (GLTFCA) links Limpopo, Banhine, and Zinave National Parks in Mozambique; Kruger in South Africa; and Gonarezhou National Park in Zimbabwe.

Future conservation efforts should focus on creating such interconnected landscapes rather than managing wildlife populations with fences and artificial water points. This conviction is core to IFAW's Room to Roam vision of securing and connecting habitats to create safe passages for elephants and other wildlife to travel freely, without human constraint, and benefit the landscape rather than degrading it. The positive outcomes of this far-reaching initiative will be greater biodiversity, natural resilience to climate change, and a future where animals and people can coexist and thrive.

Every problem has a solution, every solution needs support.

The problems we face are urgent, complicated, and resistant to change. Real solutions demand creativity, hard work and involvement from people like you.

Unfortunately, the browser you use is outdated and does not allow you to display the site correctly. Please install any of the modern browsers, for example:

Google Chrome Firefox Safari