Updates

Relief and recovery for animals and people in Myanmar

Read moreHow whale poop and phytoplankton are fighting climate change

Whales are a crucial part of the ocean ecosystem, and they’re helping to fight climate change in an unusual way—through their poop.

With the large quantities of faeces they produce, these large marine mammals feed phytoplankton which, in turn, serve as a food source for zooplankton. Both of these tiny aquatic organisms are vital to the planet’s health and form the basis of the food web. They help to remove carbon from the atmosphere, reducing greenhouse gases. Phytoplankton also produce around 50% of the oxygen we breathe.

Let’s take a closer look at the relationship between zooplankton, phytoplankton, and whales, and discover how these three sea organisms impact climate change and the health of the planet we call home.

Zooplankton are tiny organisms that live in water. They are most commonly found in oceans, lakes, and ponds. Their name comes from two Greek words—zoo meaning animal and plankton meaning drifter.

There are different types of zooplankton. Some are larval forms of sea creatures, including mussels, jellyfish, sea snails, worms, and fish. If they aren’t eaten, these zooplankton can turn into fully-grown sea creatures.

Other zooplankton are known as holoplankton. This means they spend their whole lives as plankton. Examples include krill and copepods.

Krill is one of the largest and most ecologically important types of zooplankton. They grow to be up to six centimetres (two inches) long and can live for up to five years.

Zooplankton are a source of food for many marine creatures. Their predators include small fish, shrimp, crustaceans, snails, crabs, clams, and lobsters. Some jellyfish species and some types of coral also feed on zooplankton.

The largest consumers of zooplankton, however, are baleen whales, like the blue whale. In fact, krill means ‘whale food’ in Norwegian. These whales use their baleen plates to filter zooplankton from seawater and can consume huge amounts of plankton in a single day.

Zooplankton consume bacteria, algae, and other zooplankton. They also feed on phytoplankton. Scientists group zooplankton into two groups—herbivores, which feed on phytoplankton, and carnivores, which feed on other zooplankton.

Producers—also known as autotrophic organisms—create their own food. They are typically plants and other photosynthetic organisms, like phytoplankton, which can convert sunlight into energy through photosynthesis. These producers form the base of the food web.

Consumers—also known as heterotrophic organisms—are organisms that eat other organisms for energy. Zooplankton are consumers. They feed on phytoplankton and other small organisms to obtain energy.

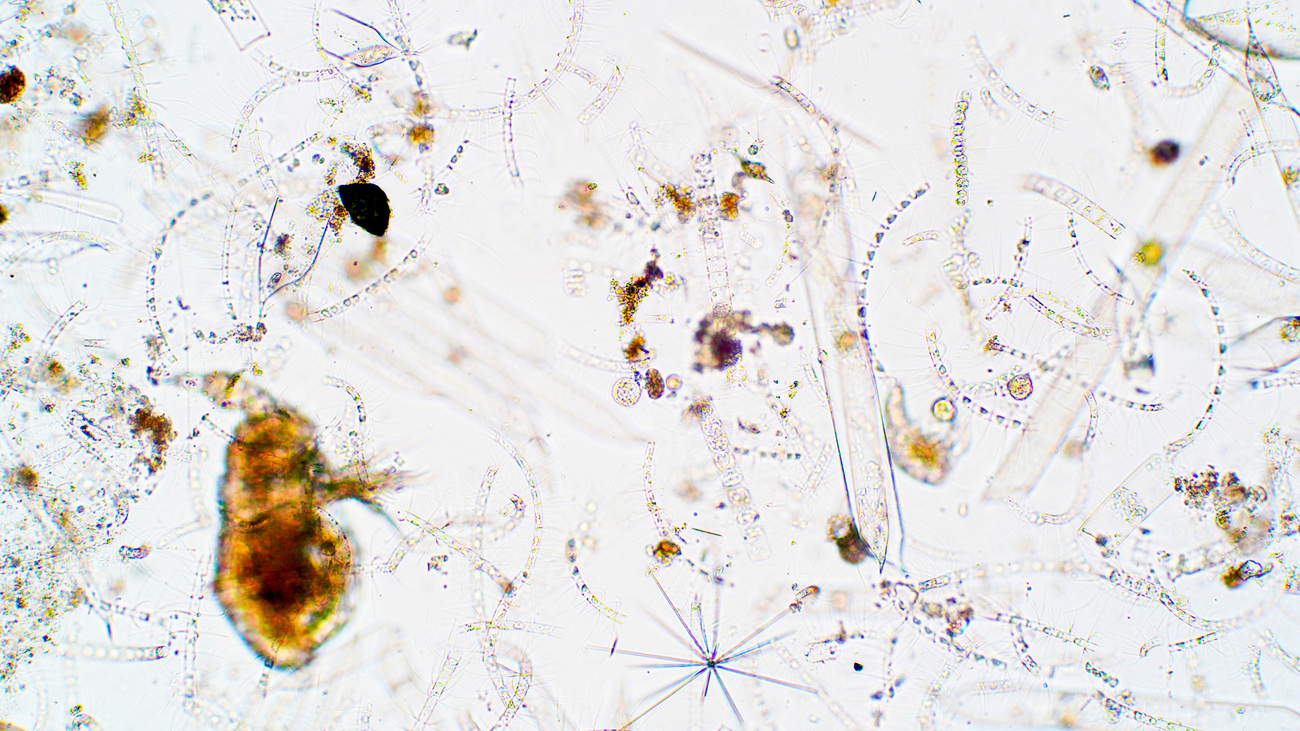

Phytoplankton are a type of floating algae that drifts with water currents. Like zooplankton, phytoplankton form an important part of the food chain. Phytoplankton live in both marine and freshwater habitats.

These tiny organisms can’t be seen by the naked eye. However, sometimes phytoplankton in large numbers can appear as colourful patches on the surface of water.

Phytoplankton are crucial to life on Earth. They produce around half of the world’s oxygen and absorb tonnes of carbon dioxide. Phytoplankton are also a key source of food for many other aquatic organisms. Some types of zooplankton, like krill, feed on phytoplankton. Small fish and crustaceans also eat phytoplankton.

As producers, phytoplankton—a type of plant—create energy using sunlight and the process of photosynthesis. This is where whale poop plays an important role. Whale faeces act as a fertiliser for phytoplankton, giving these organisms the nutrients they need to grow and flourish.

Both phytoplankton and zooplankton are types of plankton that live in water. They are tiny organisms that drift around on ocean currents. However, there are some key differences between these two types of organisms.

First, phytoplankton are plants and zooplankton are animals. Phytoplankton make their own energy with sunlight and chlorophyll. Zooplankton feed on other organisms for food and energy.

These two types of plankton are also different in appearance. Most zooplankton are big enough for us to see with the naked eye. They tend to be translucent and come in a variety of shapes and sizes.

Phytoplankton are trickier to spot. You’d need a microscope to see an individual phytoplankton organism. However, you can see phytoplankton in the ocean when they appear in large numbers. They look like a cloudy green patch in the water.

The final key difference between phytoplankton and zooplankton is where they live. Phytoplankton can be found close to the surface of the ocean. That’s because they need sunlight to photosynthesise.

Zooplankton tend to live in deep water during daylight hours. This helps them stay safe from predators. However, at night, these tiny creatures travel to the surface of the ocean to feed on phytoplankton and other organisms before returning back to the depths.

Both zooplankton and phytoplankton are incredibly important to life on Earth.

Excessive carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are contributing to rising global temperatures, impacting human health and global ecosystems. In our oceans, water temperatures and acidity levels are rising, killing coral reefs, dissolving crustacean shells, and disrupting the balance of marine life.

But plankton is helping to mitigate the effects of climate change and protect biodiversity. Phytoplankton are also responsible for producing oxygen.

Plankton are the foundation of the marine food chain. The health and productivity of all oceanic life depend on them.

Phytoplankton account for almost half of global primary production and 90% of primary production in our oceans. They are a key source of food for zooplankton.

Zooplankton are then eaten by other aquatic creatures, including fish and crustaceans. These smaller marine creatures are eaten by larger predators and so on, up the food chain.

Zooplankton are also a primary source of food for baleen whales who can eat up to 4.5 tons of krill every day.

Plankton play important roles in the Earth’s carbon cycle.

When phytoplankton die, they sink to the depths of the ocean, taking the carbon they absorb through photosynthesis with them. It’s estimated that our oceans absorb around 40% of all the carbon dioxide we produce. That’s equivalent to the amount of carbon captured by 1.70 trillion trees.

Zooplankton also contribute to this process. They rise to the surface of the ocean each evening to feed on phytoplankton. They then sink back to the depths of the ocean, where their waste sinks to the ocean floor. This also helps to remove large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere.

Phytoplankton are primary producers. That means they get their energy through the process of photosynthesis. Light from the sun is used to turn carbon dioxide into oxygen. Phytoplankton then releases this oxygen as a waste product, producing around half of the oxygen we breathe on Earth.

Whales play a crucial role in marine ecosystems. Some whales—like sperm whales and blue whales—dive deep underwater to feed on nutrient-rich prey, including zooplankton.

They then return to the surface, where they expel nutrient-rich faeces. This process is known as the ‘whale pump’, because whale movements bring nutrients from the deep sea up to the surface. The iron and nitrogen in whale poop acts as a fertiliser and helps phytoplankton to grow.

By travelling from the depths of the ocean upwards, whales help to bring nutrients to the surface. And when whales migrate to breed, they release faeces as they go, bringing nutrients to other oceanic regions. This can prompt phytoplankton blooms along migration corridors.

By supporting phytoplankton, whales support zooplankton and entire ocean ecosystems. Zooplankton feed on phytoplankton, and then aquatic animals—including large marine mammals like whales—eat zooplankton, and so the cycle continues.

Without whales, phytoplankton and zooplankton numbers would fall. Phytoplankton would find it hard to grow without regular fertilisation, in the form of whale faeces—and with less phytoplankton to eat, zooplankton numbers would also decline.

This effect has been called the krill paradox. Whales are krill’s biggest predators. But when whale numbers fell due to commercial whaling, the krill didn’t thrive as expected. Instead, krill numbers fell, too.

By supporting phytoplankton and zooplankton, whales contribute to the production of oxygen and the reduction of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere. Here are some of the other incredible things whales do for our planet.

Whales sit at the top of the marine food chain. They help to maintain balance and biodiversity in oceanic ecosystems by controlling the number of prey species.

By supporting phytoplankton and zooplankton, whales also provide a source of food for themselves and many other marine creatures. This travels all the way up the food chain.

Whales also play a role in carbon capture. These creatures are some of the largest and longest-living animals on Earth. They store carbon in their bodies, just like trees store carbon in their trunks.

When whales die, their bodies sink to the bottom of the ocean in a natural process known as a ‘whale fall’. The carbon stored inside their bodies sinks with them.

Whale falls can keep carbon on the ocean floor—and out of the atmosphere—for hundreds to thousands of years. They also provide food for deep-sea creatures.

Whales around the world are under serious threat from human-made threats—commercial whaling, vessel strikes, ocean noise pollution, entanglement, and climate change.

Whale numbers decreased dramatically when commercial whaling was widespread. Between 1890 and 2001, minke whale numbers fell by 20%, the fin whale population decreased by 85%, and blue whale numbers fell by a catastrophic 98.5%.

Whale populations are yet to return to their pre-whaling numbers and—despite a global moratorium—some countries still allow commercial whaling.

In addition, vessels regularly collide with whales on busy shipping routes, killing or injuring them. They become entangled in fishing gear, which impacts their ability to swim and feed. Ocean noise prevents whales from communicating and navigating properly.

Their habitats are also changing due to climate change. Plankton are very sensitive to environmental changes, including the temperature, salinity, pH level, and nutrient concentration of our oceans. As oceans warm and sea ice melts, zooplankton numbers are falling. The changing availability and location of zooplankton—a primary food source for many whales—is impacting whale energy levels and reproductive rates.

Without whales—and without whale poop—the ocean, as well as the planet as a whole, cannot thrive.

It’s important that we protect whale populations, helping phytoplankton and zooplankton to thrive in the process. A one percent increase in phytoplankton productivity would capture hundreds of millions of tons of additional CO2 every year, supporting our fight against climate change.

IFAW is working with partners and communities around the world to protect whales and marine ecosystems. We’re trying to save the North Atlantic right whale, which has a population of only about 370, from extinction. We’re collaborating with fishermen, gear manufacturers, and regulators to promote innovative solutions, including ‘on-demand’ fishing gear that helps to prevent entanglements.

We’re working to prevent vessel strikes by moving shipping lanes away from critical whale habitats and by imposing slower ship speeds. Our Blue Speeds campaign aims to reduce the underwater noise, the risk of collisions, and the harmful greenhouse gas emissions produced by shipping.

In Kenya, IFAW is working to safeguard coastal habitats to protect East Africa’s abundant biodiversity, which includes whale species. Whales are vital to these ecosystems, which support the livelihoods of 2.7 million people.

IFAW’s marine mammal rescue team helps whales, too. We respond to stranded whales and also perform necropsies to inform research on the threats whales face. We have also reimagined how sedation can be used to save entangled whales more effectively.

IFAW also is advocating for the end of commercial whaling everywhere. In Iceland, we’ve been working to change perceptions of whale meat. Here, whale meat was marketed to tourists as a traditional Icelandic food. Through our ‘Meet Us, Don’t Eat Us’ campaign, we’re promoting responsible whale watching as a sustainable alternative to commercial whaling.

We are working to end the whale hunt in Japan, where it recently resumed. Sign our petition to voice your support for the end of this cruel, unnecessary, and unsustainable practice.

Our work can’t get done without you. Please give what you can to help animals thrive.

Unfortunately, the browser you use is outdated and does not allow you to display the site correctly. Please install any of the modern browsers, for example:

Google Chrome Firefox Safari