How a daring team stops illegal trade of endangered wildlife in Indonesia

How a daring team stops illegal trade of endangered wildlife in Indonesia

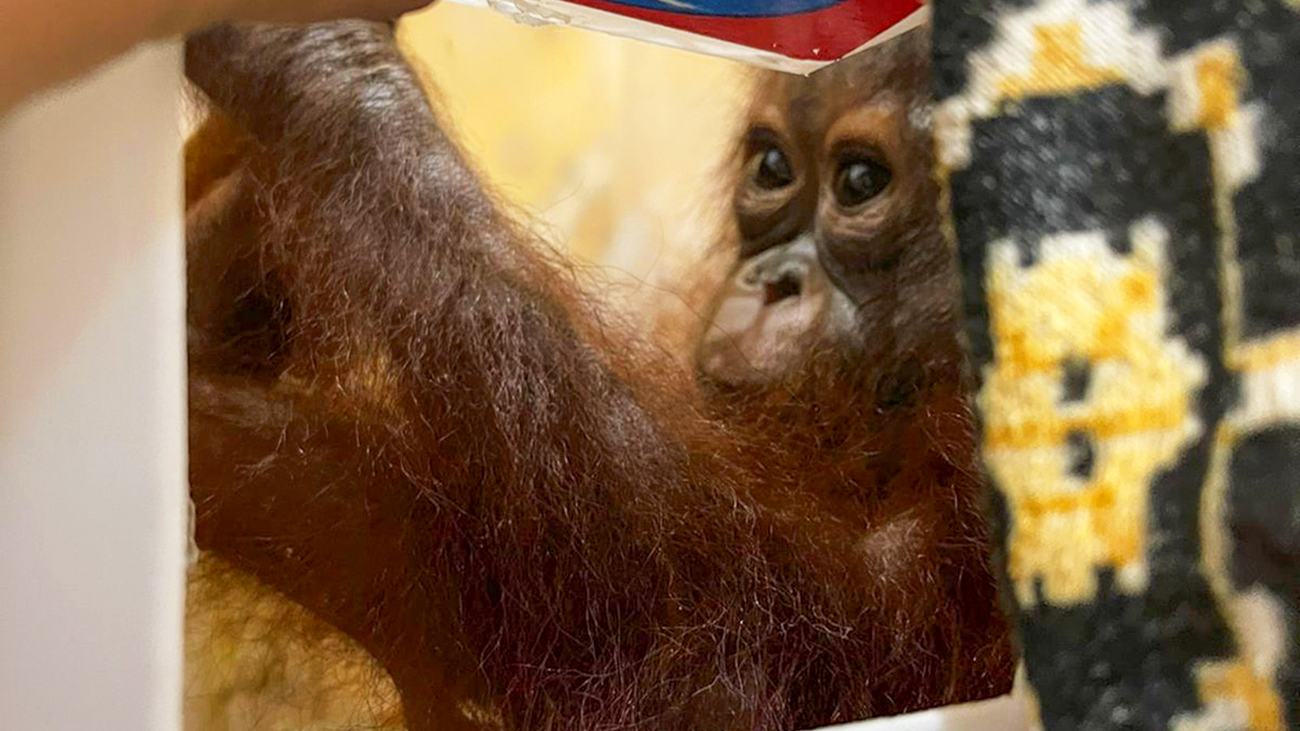

A baby orangutan. A Javan slow loris. A baby Javan gibbon. A pregnant Sunda pangolin. Two Sunda leopard cats. A critically endangered Javan leaf monkey.

All of these extremely threatened wild animals were rescued from traffickers when IFAW’s partner Jakarta Animal Aid Network (JAAN) and the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) carried out an undercover investigation aimed at disrupting online wildlife trafficker networks identified in Indonesia.

Online traffickers were offering the animals—and several illegal wildlife products made from dead animals—for sale through Facebook. Thanks to JAAN and WTI’s work, authorities are prosecuting the criminals, and specialists are caring for the animals until they can be transferred to rehabilitation centres.

A rigorous investigation

The IFAW-WTI team works round the clock, across time zones to monitor social media channels and messaging apps such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Telegram. The team collates key information on the illegal wildlife trade across the globe and shares it with trusted enforcement agencies and organisations for subsequent actions. In this case, when the WTI team discovered the illegal sale of live pangolins and orangutans in Indonesia, they shared actionable information allowing JAAN to begin a rigorous undercover investigation.

Under the guise of potential buyers, they contacted the broker. After successfully gaining the broker’s trust, they conducted an on-site visit to where the live animals or products were kept and collected evidence to confirm the trader indeed had the wildlife in his possession. Next, they collaborated with a special police unit to execute a raid.

JAAN’s co-founder Femke den Haas says, “The animals come with us. The police deal with the trader and follow up on information we can get through the trader—leading us further to the poachers, the brokers, or whoever is ordering nationally or internationally.”

One of their May arrests led them deeper into the criminal web, enabling them to rescue a ten-month-old male orangutan.

The buyers who fuel the wildlife trade

If JAAN hadn’t rescued these animals, they most likely would have become illegal pets or been exploited for entertainment in other countries.

“Gibbons often end up as a pet in someone’s house, as a status symbol,” Femke says. “There’s a lot of illegal trade happening right now from Indonesia to the Middle East, where very wealthy people like to have private collections of unique and rare species.

“Orangutans are very popular in Thailand, so the baby orangutan was destined to be used in entertainment shows in the zoos there. Luckily, we could intervene and rescue this baby.”

Risky business

Unfortunately, wildlife trafficking is a big business, with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency estimating it to be worth up to USD $10 billion a year worldwide.

Illegal wildlife traders work with brokers and poachers in ways that are akin to drug and weapon trafficking, except the criminals are often not prosecuted to the same extent.

“We’re dealing with criminal networks,” Femke explains, “and these people will go very far to stop us or the investigators from doing what we’re doing because they want to continue earning a lot of money.

“That’s the risk that everybody’s taking when we deal with this type of work.”

Why wildlife crime persists in Indonesia

Indonesia is a large archipelago and, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, “one of the world’s largest biodiversity hotspots.” Its islands are home to hundreds of endemic animals—species found naturally nowhere else in the world.

Many of those species are also endangered, and their rarity makes them even more valuable and vulnerable to exploitation.

“Sadly, all endemic animals are offered for sale,” says Femke.

“In Indonesia, there’s a lot of issues with habitat loss, forest destruction, and illegal poaching. The babies often fall victim to this illegal poaching activity, and then they end up in the illegal wildlife trade.”

Trauma of the trade

Although the animals JAAN rescues are fortunate to be saved before they could be sold, they have already suffered unspeakable trauma.

“Animals are poached by killing their mothers,” Femke explains. “Orangutan mothers will never let go of their babies, so they are killed and then the babies are separated from their mothers’ bodies. This is the same for gibbons and other primate species.”

Poachers hunt other animals, like pangolins, by fumigating their sleeping holes and dens. The stress and trauma of capture and captivity have devastating consequences. The pregnant pangolin JAAN rescued went into premature labour.

Her pangopup did not survive.

What happens next for these rescued animals—and their criminal captors

The maximum penalty for wildlife trafficking in Indonesia is five years’ imprisonment and a fine of 100 million rupiah (around USD $6,500). JAAN expects the trafficker of the baby orangutan to receive the maximum penalty.

The wildlife products JAAN discovered will stay with the police as evidence. Since the live animals are also considered evidence, they will stay in the care of JAAN and their partners until the court cases finish.

For now, the animals require a tremendous amount of continuous care. Much like human babies, the baby primates need milk every two hours.

“It’s a very critical period of about two to three months,” Femke says. “They have been through a lot of trauma and stress. Their condition is very fragile, so we need to take care of them around the clock. Once they are more stable and we receive an okay to relocate them to a better situation, they can be relocated to a rehabilitation facility, where they at least are surrounded by their own species.”

JAAN always checks the animals’ DNA to discover which island they came from. That way, they ensure the animals will be released into their home environment.

Based on his DNA, the baby orangutan will eventually go to a rehabilitation centre in Kalimantan. This centre was founded by Birutė Galdikas, one of the “Trimates”—three women primatologists who studied primates in their natural environments. While Galdikas studied orangutans in Indonesia, Jane Goodall studied chimpanzees in Tanzania and Dian Fossey gorillas in Rwanda.

How you can stop wildlife trafficking, too

“I think it’s important for the public to know that wild animals should never be kept as a pet,” Femke cautions.

“You should also always think twice when you visit wildlife in captivity. Are the animals there because it’s a sanctuary and they were rescued? Or is it a place that contributes to wildlife crime and the wildlife trade—because you should not visit those places.”

One example is zoos that use orangutan babies and juveniles in their shows.

“These orangutans were all taken from the wild,” says Femke. “They all lost their mothers, they’re very traumatised, and they are forced to work and to entertain tourists. Visiting these places contributes to the problem.”

Working with partners

Live animals rescued from trafficking don’t get as much attention as wildlife products, and IFAW realises that live seizures and confiscations are challenging and need corrective action.

Through longstanding partnerships with organisations such as JAAN and WTI, IFAW focuses on ensuring the animals survive until an approved rescue or zoo can pick them up while the legal process continues. IFAW maintains wildlife crime and rescue global projects in selected countries in Asia, Africa, and South America.

Related content

Our work can’t get done without you. Please give what you can to help animals thrive.